Copy Number Variation

Copy number variants (CNVs) occur when parts of or entire chromosomes are replicated or lost. CNVs occur in normal healthy individuals, with no outward sign of disease. However, there are diseases that are due to CNVs such as Down Syndrome, where individuals have an extra copy of chromosome 21, or Huntington's disease where a short sequence "CAG" is replicated over 35 times in a single gene. In cancer, cells with unstable genomes may duplicate sequences many times, amplifying the genes that promote the disease, or cells may drop copies of genes that prevent cancer.

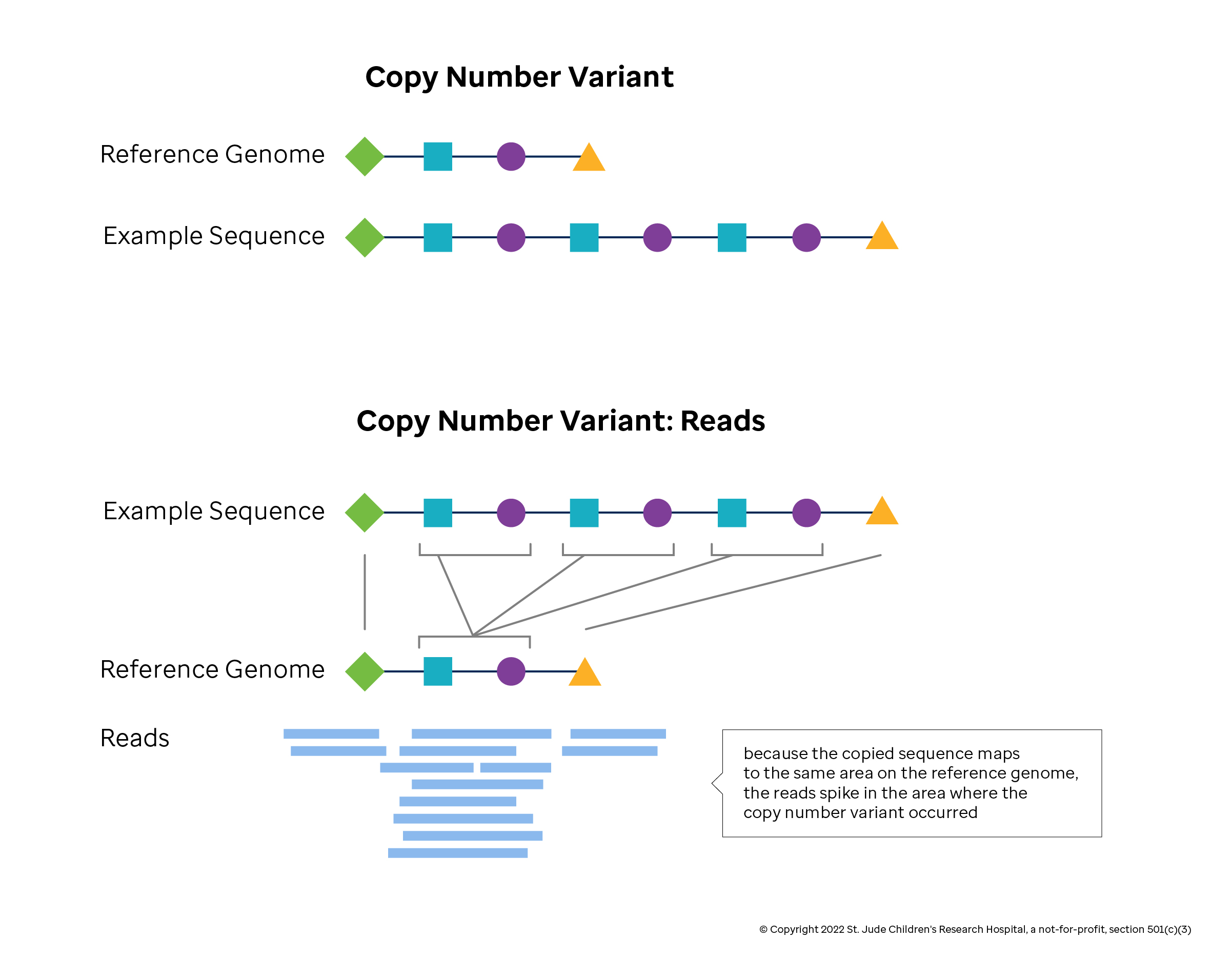

Detecting CNVs computationally from sequencing data begins by mapping reads to a reference genome and determining the read depth, or coverage. In theory, the coverage should reflect the relative copy number. In practice, some DNA regions get more counts than others simply because their sequences are more easily mapped. In addition, duplicate reads generated by lab preparations may inflate local counts, and sequence machine errors give inflated quality estimates for some bases. CNV detection methods adjust the coverage estimates to remove each of these effects. Coverage estimates at the base pair level are too small and variable to reliably define a CNV, so smoothing methods are applied to derive a mean estimate of coverage within a window, or bin. Last, CNV methods that rely on read depth identify the boundaries of CNVs regions through segmentation or modeling methods.

In general, CNV detection methods further refine their search by comparing normalized coverage estimates to a panel of normal control genomes with the expected two chromosomal copies. In cancer, the mapped counts from a tumor sample are often compared to a normal genome from the same patient to further refine the analysis. This comparison identifies changes due to disease rather than the patient's natural variation.