Structural Variation

Living cells are remarkably tough in that they can tolerate large scale changes (>1,000 bp). These large-scale variants, called structural variants or SVs, can play a role in cancer and other diseases.

Structural variations take many forms—sequences may be deleted, copied, moved, inverted or exchanged between chromosomes. These changes vary greatly as some SVs are complex rearrangements involving multiple chromosomes while other SVs may only disrupt one part of a single chromosome. SVs are distinguished from indels by their large size, although there is no standard accepted threshold. While SVs are detected computationally, some SVs are large enough to be seen in an ordinary microscope.

After an SV event the original genomic sequence is interrupted by another out of place sequence, creating a breakpoint. Detecting breakpoints in SVs requires specialized computational methods. One strategy is to pull all of the reads that are high quality but do not map to the reference genome as expected, split them in two and remap the pieces. If the read overlaps the breakpoint, the two pieces both map but to different locations. This is called a split read. If multiple unique split reads map to same locations, on both strands, there may be enough evidence to call breakpoints. Discordant paired end reads, where one read maps to one chromosome and the second to another chromosome, also lend support to breakpoints.

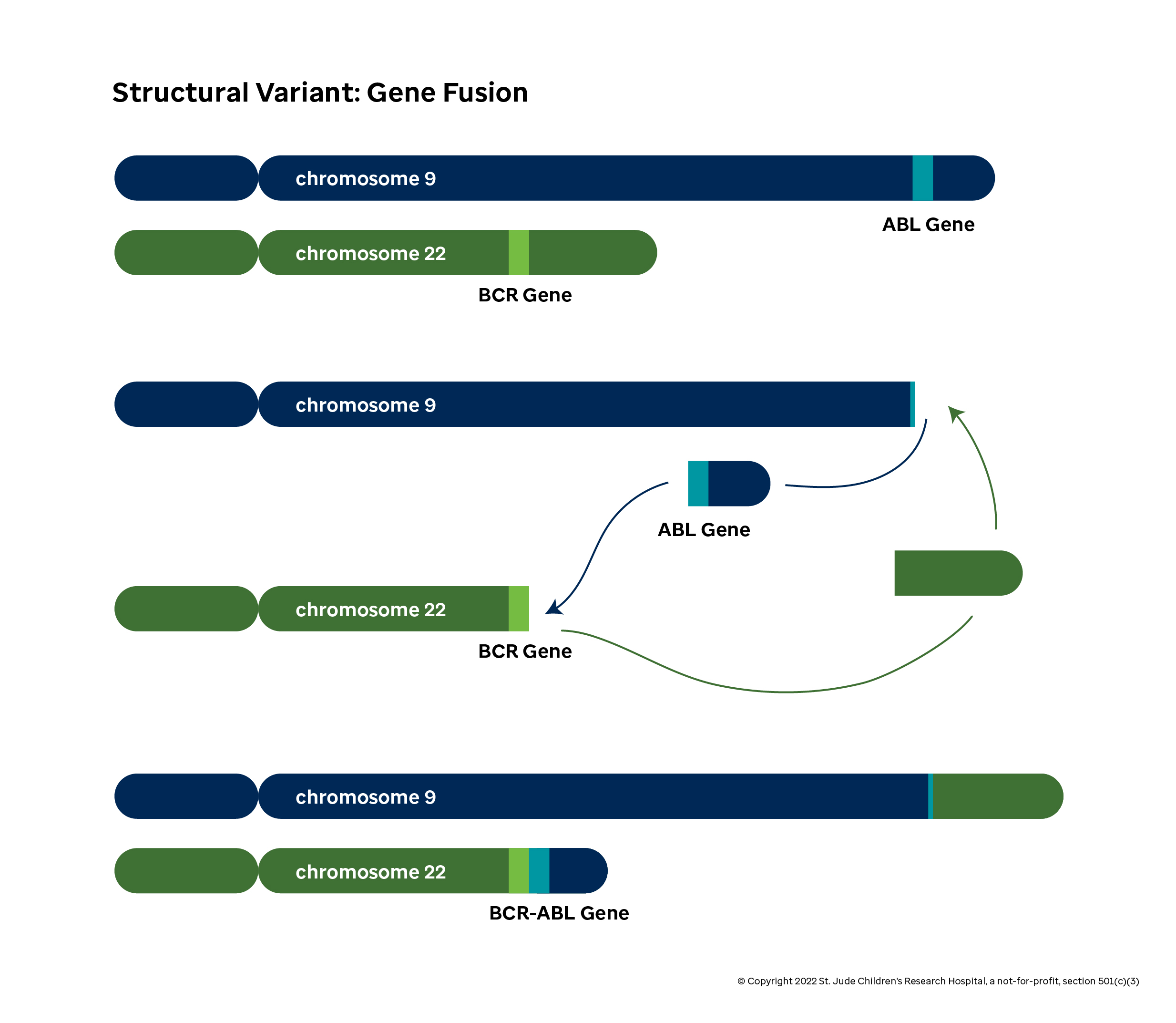

Gene Fusions

For SVs, what happens at the breakpoint matters. Often DNA breaks interrupt coding regions, separating the exons of specific genes. When multiple chromosomes are broken, the pieces of DNA from different chromosomes are joined together. When the rearranged DNA is translated into RNA, some, or all, of one gene's exons are spliced to the exons of another gene. These novel sequences are called gene fusions and are potent drivers of cancer. Gene fusions that are translatable will generate hybrid proteins with a combination of the functional sections (or domains) from the original genes. Often these hybrids act in ways the cell is not prepared to handle.

Consider the case of the well-studied BCR-ABL1 gene fusion (or Philadelphia chromosome). This effect of this fusion becomes apparent when you look at the distinct functions of the BCR and ABL1 genes in normal cells:

ABL1 is involved in cell proliferation and replication. The protein has a domain (specifically, the tyrosine kinase domain) that transmits a signal telling the cell to replicate by dividing. When functioning properly, the cell creates ABL1 proteins to drive normal cell growth as needed.

Unfortunately, the function of the BCR protein in normal cells is not well known at the time of writing. What is important is in this case is that the cell will produce BCR at different levels than ABL1 depending on the scenario.

In some leukemias, the front half of the BCR gene is fused to the back half of the ABL1 gene. When the cell machinery attempts to produce the BCR protein, a hybrid protein containing the tyrosine kinase domain is produced instead. This can lead to many additional copies of the problematic domain floating around than the cell intends, which causes the cell to divide much more than it intends and can ultimately be a driver for cancer.

Detecting fusions like BCR-ABL1 is an important part of cancer diagnosis and influences the choice of treatments a patient receives. Like breakpoint discovery, many fusion detection methods rely on finding split reads and discordant read pairs that map to two genes called spanning reads. These reads are rare in genomic sequences, so fusions are generally detected using RNA-seq. Fusion detection methods may also enhance their sensitivity by testing for known fusion sequences or by testing against a database of potential fusions based on known exons.